John’s first story, written when he was 17 year’s old

The old men slowly shut his textbook and rose from the

table. Carefully he gathered the

dictionaries and exercise books, sorted them so that the largest was at the

bottom of the pyramid, and placed them in the corner of his oak desk. The boy stood up and stretched. The end of another lesson. Another timeless interval of confusion,

lightened by the enthusiasm of his teacher, and warmed by the knowledge of

occasional achievement.

“If you would

like to draw the curtains, I’ll see if I can’t rustle up some tea.” The old man disappeared into the kitchen, and

the familiar sounds of preparation started to fill the house. The boy went to look out of the window.

Great clouds of darkness hung in the skies,

disappearing in random series of silver and grey towards the imperceptible line

that separates the sky from the sea. The

water held a heavy broodiness broken only by that glint of foam that indicates

the first pain of a wave’s death-throe on the cliffs below. Away to the west, the last of the day’s sun

was stretching long lines of light across the bottom of the clouds. Soon it would be dark.

Slowly the boy drew the curtains and shook them so

that they overlapped. He turned to the

fire added another log, and lazily poked the embers into life. Then he lowered himself into one of the

wing-backed armchairs and allowed himself to become mesmerized by the flames in

the hearth. His ears caught the sound of

the boiling kettle, and the creak of his teacher’s shoes in the kitchen.

There was a curious bond of love between the two,

built on the fear and respect of the boy, and the kindness of the old man. The boy hated the rigid discipline and

infinite knowledge which his teacher would bring to bear on every question; and

yet revelled in the vast horizons which were opened up by the same erudition. While the old man envied the earnestness and

frenzy of his young pupil. Each gave to

the other of their utmost, and in giving, learned more of themselves.

The muted clatter of the trolley heralded the arrival

of tea. Vast cups of china tea, with no

milk and a piece of lemon, floating. Plates

of hot-buttered toast which would be placed in front of the fire, and hastily

consumed before they became dry. Pots of

honey and Gentleman’s Relish. Silver tea

spoons and large saucers, and the second cup which always tasted better.

The sound of the waves and the rising wind of dusk

served to emphasize the warmth and peace in that circle of light around the

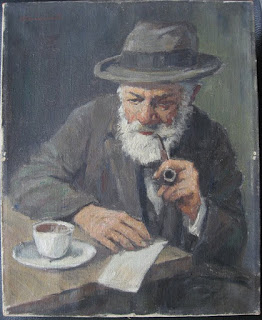

fire. The old man sat back and performed

the careful ritual that culminated in the first languorous spiral of smoke escaping

from his pipe and expanding towards the darkened ceiling. He crossed his legs, brushed some ash from

his lapel, and cleared his throat.

“If I teach you

nothing else, I would like to think that there is one thing you will have

learned from me.” The boy made himself comfortable. It was unusual for his teacher to talk,

preferring merely to encourage his pupil’s mind with the odd interjection. But when he assumed the attitude of raconteur,

the boy had learnt to listen, as the old man conjured up dreams that made up

for more than all the hard lessons he had to suffer.

“When I was

young, there was a girl. She was tall

and winnowy, with dark black hair and eyes that started black and disappeared

into an impenetrable depth. When we

talked, I had the impression that there was always another listening, for she would

never look me in the eyes, and her answers contained more than I could understand. The French call it an ‘arrière-pensée’. At no time did she give me the slightest sign

of affection, or acknowledge that I was anything than another person of her

acquaintance. Yet she held over me a

spell that made it difficult to think of anything else. I would spend hours recollecting the careless

gesture with which she would toss her hair from her eyes, or the innocent

intensity which came over her as she recited her prayers in a pew, before going

up to play the organ for Evensong.

I was a curate then in a small parish in the West

Country. With the zeal and enthusiasm of

youth I had dived headlong into the vocation, and devoted my every waking hour

to the service of my vicar’s parish. The

people would talk of my conscientiousness, and I was proud to be an instrument

of God's work.

Then one day she arrived. I never found out where she came from. She simply walked into the vicarage, and asked

the vicar if she could play the organ for him.

He had called me, and the three of us had gone over to the church to hear

how she played. Up till then I had

played the organ, but was the first to admit that my loud chords and carefully

rehearsed hymns lacked that gift which the Lord should expect in his house.

She sat down and started to play. It was one of Scarlatti' s early tunes. She had barely had time to develop the first

theme when I turned to the vicar and nodded.

He smiled back, and I knew he was pleased that I had accepted. She started the next Sunday.

Every Sunday was the same. Arriving exactly half an hour before the

service, she would bend herself in prayer, and then as the five minute bell

started to toll over the countryside, rise and go to the organ. After Matins she would take dinner with us at

the vicarage, after which she would sit by the fire reading one of the

leather-bound books from the vicar’s library.

She would choose one of the Latin poets or occasionally one of the Greek

philosophers. She would sit so still when

reading that only the turning of a page would suddenly remind me she was still there.

At tea she would act as the hostess, carefully adding

the milk and sugar, and handing around the crumpets. The vicarage was not given to light

conversation, especially on a Sunday, and only once did she ever become

involved in a discussion. The vicar had

commented on an article in the popular press.

It seems that there had been some curious happenings in a church in the

north of England, which had culminated in the vicar hanging himself from his own

bell rope. Suddenly she had focused an

intensity of concentration on the conversation that left us without words. For more than an hour she had discoursed on

the power of the devil, and the inability of the church to defend itself from

his incursions. It was certain that she

had more to say, and with the aid of hindsight, I am sure that we should have allowed

her to say her peace. However, the vicar

had wanted to clear the autumn leaves from the churchyard before Evensong. She had gone to sit in the church, while we

stripped to our shirtsleeves and laboured to complete the task before the

congregation arrived.

The service that evening produced an intensity and

profundity that bound every last man of the dutiful parishioners. Never had the vicar spoken with more fervour. Never had the people sung with such fear. I could feel the awe of the voice of God

within me as I read the lesson. It was

the twenty first chapter of the book of Revelations. The one that starts: ‘And I saw a new heaven

and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and

there was no more sea.’ I remember the echo of my voice in the silence of the

church; ‘I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end’ and the joy that came

over me as I read the final verse; ‘And there shall in no wise enter into it

anything that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a

lie; but they which are written in the Lamb’s book of life.’

As I closed the book and stepped from the lectern, the

choir rose. The introduction to

Stanford’s ‘Te Deum’ rolled out from the organ, and then the whole church, as one,

launched into the glorious psalm; ‘We praise thee O God, We acknowledge thee to

be the Lord.’ Exhilaration filled the church as every man emptied his soul into

his voice, and sang praise to his Lord and Maker. The magnificent sound hung in the rafters as

the choir filed out of their pews and walked before me to the vestry at the west

end. As we passed through the body of the

church I could see an exhausted happiness on every face. A glow that shone from every eye. The vicar closed the door behind us and we

knelt in prayer. I could see him

sweating in the knowledge of the power that had been unleashed in his church.

He joined us on knees and crossed himself, opened his

book, found his place, lifted his head and made as if to speak. But he never spoke.

From the church came the sound of the organ. A voluntary was being played. There was in that very first chord, a threat

so terrible that the vicar was unable to speak.

The deep bass pipes were growling through the foundations. A multitude of strange harmonies filled the

air. The music carried a depth of

feeling beyond my knowledge, rising and falling in great crescendos that fought

with my soul. It was not a tune of joy,

nor of praise. The terror and the awe

showed a knowledge of unlimited pain, of unknown depths of despair, of a fear

and dread which will echo through the heart of every man who heard those

strains till the day he dies.

Onwards the enormous sounds stretched, telling of

anguish and fear, of a soul lost beyond time itself. It was not the music of God, nor of mortal

men. An evil intent began to permeate

the themes, perpetuated in heavy discordant chords, and caught in another and

more aweful theme. It was as if the

organ itself was alive, writhing and heaving in some primordial death-throe. The music lost all semblance of tune. Wave upon wave of terrifying sound reverberated

over me, driving me down and in, till I felt like a mouse hypnotised by the

club hovering over its head. On and on

came the aweful music, till it seemed that the whole world was filled with its

terror.

My hands began to hurt. I noticed that I was still holding the great cross,

clutching it to me till my knuckles were white.

Slowly my eyes travelled up its long stem to the carving of Christ

hanging from its crosstree. His head

hung in death. And yet I saw the benign

goodness that the carver had written on his face. The power of his love came to me, fighting

the sound of the organ.

My eyes took in the scene before me; the vicar had

collapsed. His eyes were open and vacant. Around him knelt the choir, hypnotised into

statues. Slowly, using the cross, I

pulled myself to my feet. I felt the

power of God surging through me. I turned

and opened the vestry door. I braced

myself as the sound overwhelmed me, fighting to maintain my feet against the cacophony

of sound. The ugly torrent eddied around

me, seeking to push me back. I took a

breath of air and forced a step towards the altar. I held the cross in front of me. A protection against the sound. Every pace was a pain. Every breath felt like a mouthful of fire. My head was filled with noise upon noise. Evil filled the church.

The pillars seemed to have lost their dimensions. The gravestones in the walls were alive. They breathed, larger and smaller. The pews jumped up to hit me in the face,

then retreated into an infinitesimal distance.

The congregation seemed stunned. Their

unblinking eyes stared with the fear of small children. I battled up the aisle. Every step was its own future. My life was concentrated into placing one

foot in front of the other. The altar

seemed to get farther and farther away. I

felt, an exhaustion overtaking me. Suddenly

the chancel steps were before me. Like

an old man I climbed each tread. Placing

my feet as if to avoid glass I surmounted the steps and turned the corner of

the screen. My hands gripped the cross

as if it were a lifebelt. Sweat poured

down my face. The salt made my eyes

blink.

At the organ she sat.

Huddled in a black gown. Her arms

worked the keys like a dervish. Her feet

were racing across the peddles as if she were on a tread mill. Only her head, black hair falling below the

choir cap, was immobile. In the mirror

over the music rest, I saw her lift her eyes.

They saw the cross I carried.

It stopped. The

music stopped. The echoes hung in the

roof, then died. Suddenly everything

slowed down. A silence, a solid silence

filled the church. I could make out the

noise of the trees in the churchyard. Somewhere

a sparrow was chirping. I stood rooted

to the spot. I was unable to move.

Her body gave an involuntary shudder of relief. Slowly she lifted her feet from the peddles,

closed the keyboard and turned, swinging on the organ bench till she faced me. Her eyes were helpless. She lifted a hand to me. I raised mine to her. A gratefulness covered her face. I was in a dream. She came up to me and her eyes thanked me

with a simplicity that wrenched my heart.

Together we turned, and passed around the screen. Together our feet took each step down the

chancel.

She stopped. The

congregation were watching. Every face

was turned towards her, and on every face was the look of revenge. A hatred, a spitefulness, an anger filled

their bodies. They were rising. They filled the aisles. From every pew they poured forth, and came

forward to whirl like an eddy before us.

In every eye was the same violent motion that said ‘kill her’. An inarticulate murmur came from them. It developed to a growl then to a roar. The roar of an animal. An animal defending its young. Men’s shoulders were working them to the

front. Women were pulling themselves

forward with their fingers.

I looked back at her.

She stood alone. Straight. Her face held terror. A knowledge of what must come. But she didn't move. Her hands hung at her sides. Her hair ran down her shoulders. She faced her fate.

I saw my hand lift and place itself on her shoulder. I took a pace. The congregation froze. It didn't move. I put out my other hand, lifting the cross out

in front of me. The voices stopped. Slowly, reluctantly, they pulled back. She came with me. We reached the stone aisle. I could hear my shoes. The leather heels punctuating the lighter

tread of her step. We floated down the

aisle. The footsteps echoed as if the

church were empty. We turned by the

table with the hymn books. I opened the

door.

Evening floated through. Sunlight faded the world into peaceful tints. Birds called each other. The shadow of leaves on a branch. The white of the evening clouds. The dull red of the barn over the way. I stopped.

Her hand reached out and touched mine.

It said ‘thank you’. Nothing else. There was nothing else to say. Then she walked on. Out of the porch. Along the freshly swept path. Through the wooden gate and away.

I stood there. Long

after she had disappeared from view I remained, holding the cross in my hand. After a while the congregation came out. Slowly, in twos and threes, silently, passing

me on either side. No one looked at me. The church emptied. I could hear the verger clearing the pews. I could not move. The vicar appeared. Stopped.

Cleared his throat. He knew he

could not help me. Quietly, regretfully,

he turned away, and walked back to the vicarage. Last, came the verger, but I stood there still,

long after the sun’s rays had been lost from the highest clouds. Until the stars came, brightly heralding the

moon.”

The old man paused.

Slowly he knocked out his pipe, filled it, lit it, sat back and added;

“I have never entered a church since that day.”

The fire had nearly died, but the boy didn’t move. He neither knew the time nor cared. The evening became night. The wind’s boldness seeped into the room. The old man began to breath heavily, as if

sleeping. The last glow faded from the ashes. The boy could hear the waves, breaking in

monotonous rhythm, vying with the regularity of the old man's breathing. The sound gave a lulling effect that cradled

him toward sleep.

He found himself awake. It was still dark. The curtained room was impenetrably black. He had heard something. He strained to listen. All he could make out was the same dull rhythm

of the waves, and the occasional rushing which indicated the passage of a gust

of wind. Slowly he realized that he

hadn’t heard anything new. He had not

heard a noise which should have been there; the breathing of the old man. Across the cold hearth he could just make out

the shape of his mentor's knees, but no sound came from the old man. All that night the boy sat, awake, without

moving.

In the dawn he rose.

Quietly he let himself out. The

dawn carried the tidings of the new day to him as he strode along the cliff

path. The grass was wet underfoot. The sea seemed calmer today.

A seagull got up from under his feet. Screaming, it wheeled and soared down the

length of the cliff.

O to fly through the sharp early days of May

or glide lazily along the heat of summer day.

To turn and swoop and curve and climb

and sweep through birch and beech and pine.

To race along the breaking edge of surf

or hang in the updraft of a blunt cliff face.